Building a Suitable Project with an Adaptive Action Plan

As a science research mentor, your first task is often to come up with a reasonable project for your mentee. There are many things you may want to consider:

- Choosing an essential part of your project can add significance to the mentee’s contributions and can streamline the time that you invest in your mentee as it is clearly furthering your own research efforts

- Choosing an offshoot of your project can give the mentee more freedom to explore the topic based on their own interests or experience, and provides a lower-stakes environment for failure

- Choosing a project too far from your main work or expertise can be challenging—remember that mentoring does take a lot of time and investment, especially up front

Or from another angle:

- Providing an initial experiment to try with a “let’s see what happens and go from there” attitude can be exciting for you, but may be a bit aimless for the mentee

- Structuring a project can feel daunting as we often find that science throws us curveballs; however, much of this post will address this particular theme and encourage you to be structured (and also adaptive) in your project’s structure and can work for both essential and offshoot projects. This is the Adaptive Action Plan.

“Adaptive Action Planning” is a technique used in employee on-boarding, project management, and other processes, where work is divided into 1–2 week cycles of planning, action, and revision. For example, in onboarding, one form of structuring these cycles is the “30-60-90 Plan,” where goals are laid out for the new employee at the 30-day mark, the 60-day mark, and the 90-day mark, with a commitment from their manager to revisit the progress and adjust course as needed at each of these milestones.

An Adaptive Action Plan for Mentored Research

An action plan structured with iteration and revision can fit well with the plans often made for scientific experiments. We suggest using a rapid version of this for planning to mentor a summer student or other short-term mentee by establishing milestones of success for every two weeks, with weekly meetings on progress to give time for frequent feedback and revision toward the milestones and larger project goals (e.g. results for their poster, completion of a defined body of work to which they have some ownership, the potential for autonomy, etc.).

This type of explicit planning can substantially improve communication and expose differences in expectations between the mentor and mentee. If the mentee can see from the beginning where you hope that they will be at the end, they are better able to take responsibility, and build independence toward these goals. They may also be better able to ask for help since they will at least know what to ask about. It can also be a very helpful learning experience as a mentor to reflect at the end of the summer on what goals were reasonable to achieve in this timeframe — this can help with future project planning, grant writing, and mentorship as you continue in your scientific career!

For example, summer students’ final poster presentations provide a way to structure the components of their research into familiar parts of the research process. Not all students have final results for the poster and that is okay; however, the student’s work should fit into a story and not just be disconnected or repetitive tasks supporting your research agenda.

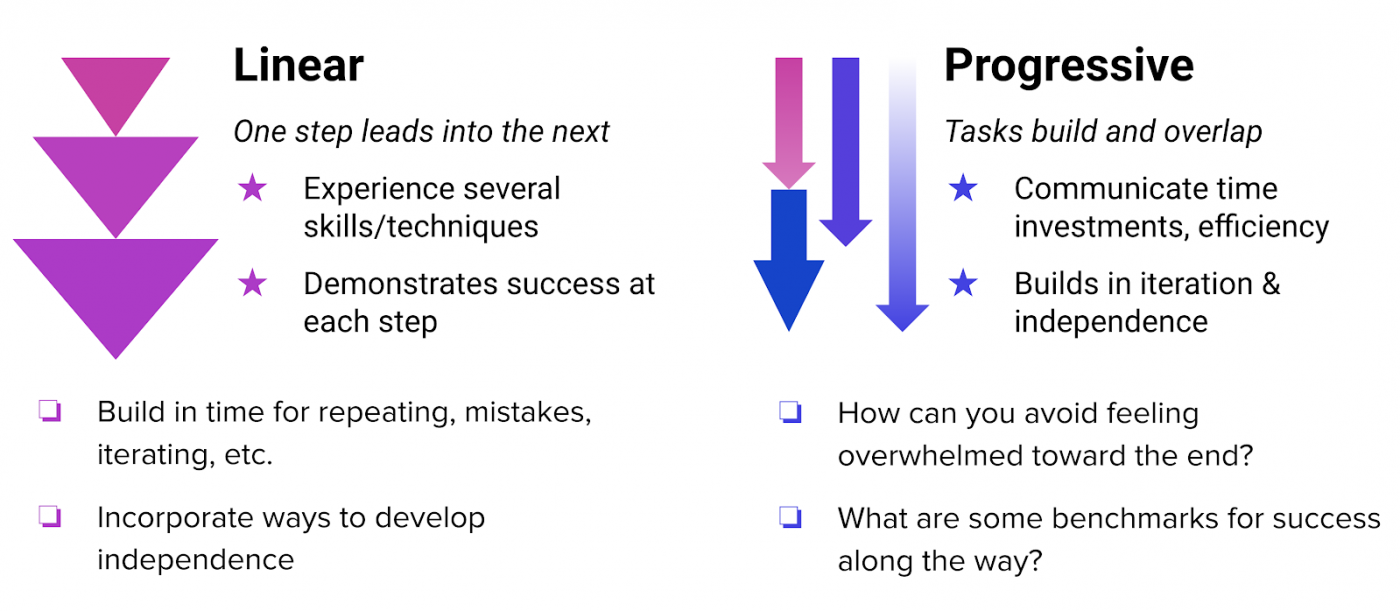

It is also helpful to think about the nature of the research project you would like to develop for your mentee. For example, will the project involve a set of linear steps where one leads into the other? Or will the project involve a set of steps that can be done in parallel, or overlap in some way? Or perhaps there is a little bit of both… Whatever the project format, incorporating time for mistakes/redos, assessment and feedback, as well as knowing approximately how much time should be invested at each step along the way, will keep things running smooth (well, at least as smooth as possible).

A Word on Goal Setting

When conducting scientific research, we often set out with an intended outcome in mind. Perhaps we hope to make suitable crystals for solving a protein structure, or we are hoping that our CRISPR’d animal model will replicate a particular aspect of a human disease. Whatever the case, it is common for us to set a research intention, and then work backwards to figure out the steps required to get there. The same strategy can be used for mentoring.

Using an Adaptive Action Plan can help articulate a set of goals for our mentoring partnership, including both scientific and professional. Once these goals are realized, we can work backwards to outline a set of actions that work toward meeting them. This process of working backwards from a stated goal is known as backwards design, and is a strategy developed to promote clear, effective planning with the end-goal in center focus. This may feel like a challenging exercise when there is a level of uncertainty inherent to any basic research mentoring situation. However, being clear and realistic about goal setting is a great first step in creating a successful mentoring partnership.

To help establish clear and realistic goals for you and your mentee, check whether they are S-M-A-R-T:

- Specific (What will your mentee do? Define it clearly.) I

- Measurable (How will they know when they’ve done it?)

- Attainable (Is it possible in their context?)

- Relevant (Does it contribute toward the final poster/story?)

- Time-Based (When should it be complete? How long will it take? Be specific.)

When building a set of SMART goals for your mentee, it is helpful to consider a few angles, as well as assess your mentee’s skills inventory. Using the backwards design approach, think about what you want done by the end of the mentoring partnership, and put this in context — what skills do you need to develop in your mentee to reach your preferred outcome? Is this skills acquisition realistic? What assets are you able to bring to this mentoring partnership? Can you articulate what success and failure might look like?

Adding onto the creation of SMART goals, we also must build in checkpoints to ensure trajectories are on target. Assessing project/mentee progress isn’t as simple as saying “I want my mentee to test the functionality of my engineered protein in cells.” How are you checking if the steps your mentee is taking make sense, and are paced appropriately? Here are some other aspects to consider when creating a set of SMART goals for your mentoring partnership:

Establish a weekly meeting for reflection and suggestion

Set a dedicated time each week for you and the student to reflect on the progress you’ve both made toward your mapped out milestones. These meetings should provide informational inputs so you can revise or sharpen your strategy, or even adjust what the milestones are (or both!). This exercise is central to reflection, iteration, and learning through the process of science. What works best? Determine the time and place, and no matter what, make it official and stick to it! Be sure to bring your Adaptive Action Plan, and make adjustments each week as necessary.

Determine a set of realistic benchmarks that are tangible representations of the work you and your mentee are doing together.

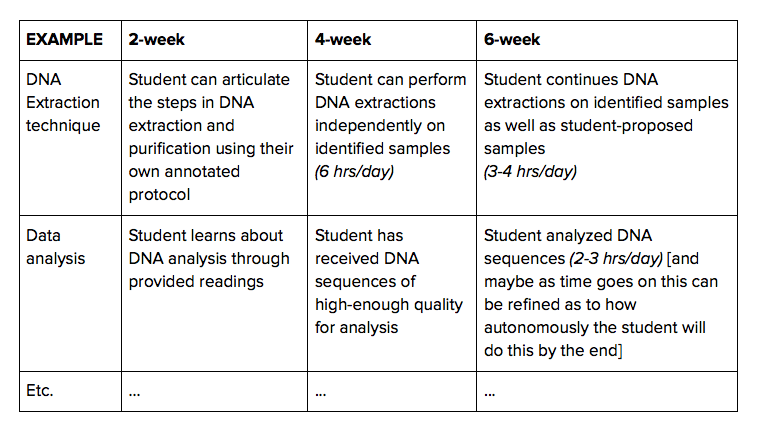

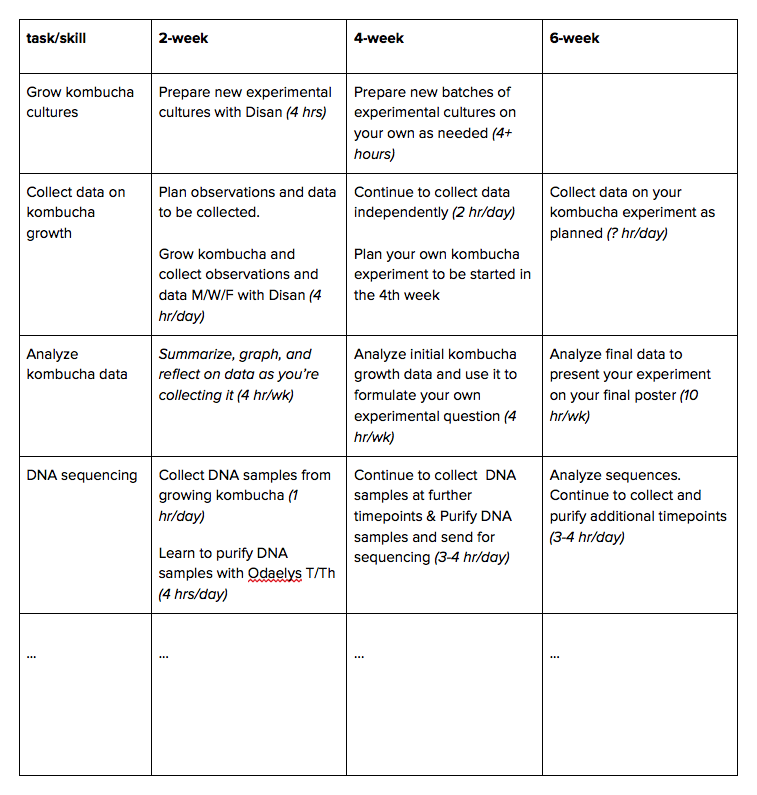

You don’t have to include every detail in this plan, but rather focus on the threads where you expect the student to progress in output, autonomy, etc. through the course of your time together. One format for structuring this level of detail is in a table where you identify a few skills/processes/outputs and the expected milestones at regular intervals (see an example of this format below for our ~7-week summer program broken into 3 2-week segments).

Map out how much time you expect your mentee to spend on defined weekly tasks.

This could vary a lot by experiment or by week, but communicating this to your mentee is helpful for setting expectations and experimental goals. Building off of the example above, it might be helpful for your mentee to see that most of their time will be DNA extractions up to the 4-week cycle, but by the 6-week cycle they should be more efficient and able to do both their DNA extractions and analysis.

Considerations for Making a Plan that is Actually Adaptive

It is always helpful to think about which aspects of your mentees project are rigid, and where there is some flexibility. Categorizing your goals into “absolutely must happen,” “would be nice if this happens,” and “if there is extra time,” can help generate a manageable set of expectations. Keep in mind that what we plan and what actually happens can be different, so it is also helpful to have a backup plan, or at least consider what the project would like like if you needed to slow down or speed up to accommodate the pace of your mentee. And, again, always, Always, ALWAYS build in time to collect and reflect on feedback.

Proposed Adaptive Action Plan Skeletons

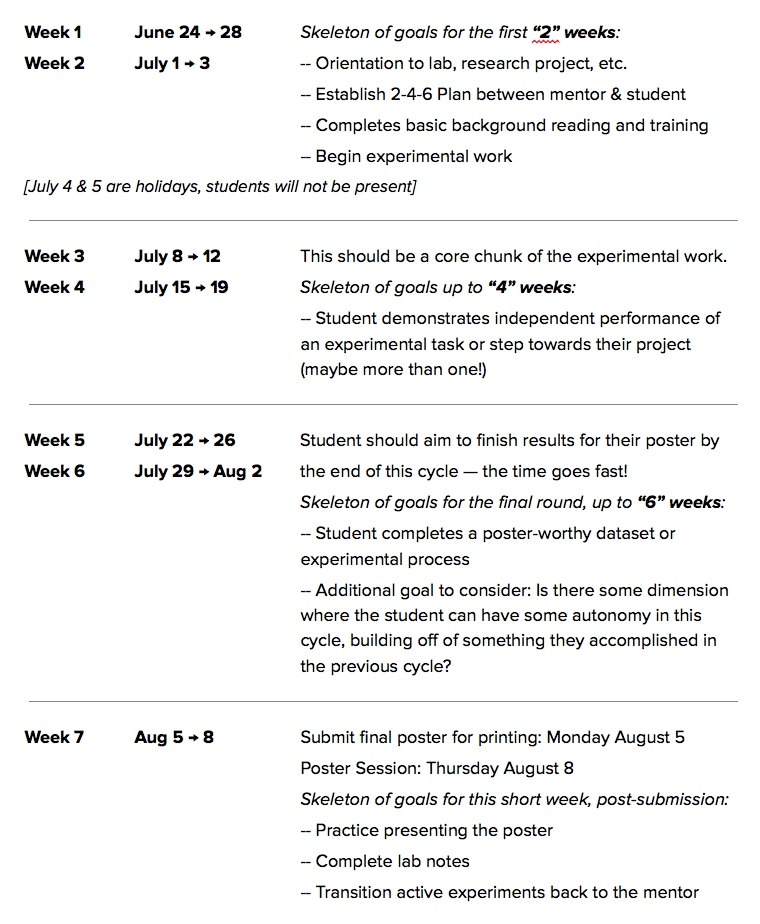

For example, for the Rockefeller SSRP, mentors have 7-weeks with their mentees, so we propose breaking the time up into 2-week chunks (aka the 2-week, 4-week, and 6-week products) and a 7th wrap-up week to produce final output, wrap up loose ends, and clean up. Informally, we call this the “2-4-6” plan. Two different formats for outlining a project in this structure are featured below:

Example of final week wrap-up notes for research projects of set length:

- Make sure DNA samples in the freezer are clearly labeled or thrown out.

- Clean up all kombucha jars from your experiments, leaving the mother culture to continue to grow.

- Photograph and then throw out all kombucha plates or other leftovers from experiments or data collected.

- Make sure any samples left in the lab for continued study are clearly documented in your lab notebook with future instructions.

Others helpful resources include:

https://phys.washington.edu/sites/phys/files/documents/grad/phd_mentorcommunicationcwd.pdf

https://www.hsdinstitute.org/5.1.2.1-guide-adaptive-action-guide-2016.pdf

You can find a blank template to create your own Adaptive Action Plan under Save & Share to the right!